When RUTH was published in 1853, Mrs Gaskell was sure it would be too disturbing for the Victorian readers, it would be surely condemned as “unfit subject for fiction”. Instead her bravery and mastery were rewarded by the favourable, thoughtful and often lengthy notices her second novel received. She had already published MARY BARTON in 1848 describing the appalling living conditions of factory workers and their families in Manchester. RUTH, instead, is about a fallen woman, seduced and abandoned with child. The challenge issued by Elizabeth Gaskell was not in introducing such a woman as a character in one of her novels but in placing her not at the margins (where many such women appeared in Victorian fiction) but rather at the centre of the story, since Ruth Hilton is, in fact, the heroine of this novel.

The Victorian frame of mind was characterised by extreme prudery and strict morals and the fate of the so-called “fallen” women was being rejected, living as outcasts with their children, being very often forced to get a living from prostitution. What Gaskell tries to convey is sympathy with a conventionally unsympathetic character and situation. She dared defy the stiff perbenism of her middle-class readers writing a tale based on the real-life events experienced by a young unmarried mother whose cause she had personally taken up.

The Victorian frame of mind was characterised by extreme prudery and strict morals and the fate of the so-called “fallen” women was being rejected, living as outcasts with their children, being very often forced to get a living from prostitution. What Gaskell tries to convey is sympathy with a conventionally unsympathetic character and situation. She dared defy the stiff perbenism of her middle-class readers writing a tale based on the real-life events experienced by a young unmarried mother whose cause she had personally taken up.RUTH tells the story of a girl of respectable parentage, now orphaned and apprenticed to a dressmaker, who is seduced by a young squire, Henry Bellingham. When Bellingham abandons her in the Welsh village where she and her lover have been living, Ruth, pregnant and despairing, is rescued from attempted suicide by a dissenting minister, Mr Benson. He and his sister, Faith, subsequently take Ruth into their home in the northern English parish of Eccleston where Mr Benson serves, passing her off as Mrs Denbigh, a relative and widow. Under the shelter and tutelage of the Benson family home, Ruth enjoys a respectable existence for many years, bringing up her son, Leonard, and acting as daily governess to the children of Mr Benson's foremost parishioner, Mr Bradshaw. Ruth's identity and history are exposed however when, by unlucky coincidence, Bellingham (now Mr Donne) is returned as Member of Parliament for Eccleston. Following her own, and the Bensons' disgrace, Ruth devotes herself to caring for the victims of a typhus epidemic in the town and is finally acknowledged as a very generous kind creature.

The cruelty of Victorian morality's hypocritical "double standard" is depicted by Gaskell in several episodes and characters in this novel:

· Sally, the Bensons’ faithful servant, immediately understands Ruth’s real situation but accepts silently the fact that her beloved master has brought her into their home. Anyhow, she decides to punish the girl cutting all her beautiful locks and proposing her to wear a widow’s cap (p.121)

· Miss Faith Benson’s suffered acceptance of Ruth and her illeggitimate child must be worked on by her brother, Mr Banson, who seems Mrs Gaskell’s spokesman in more than one moment (pp. 100 -101)

· Mr Bradshaw’s harsh words express all his contempt – and that of the majority of the Victorian middle-classes - as soon as he discovers that the kind angelic woman, Mrs Denbigh aka Ruth, whom he trusted and appreciated so much as his own daughters’ governess, had had her child out of marriage .(pp.277-279)

These are just few examples of the attempt of the authoress to oppose the prevailing cruel hypocrytical outlook on the problem. Her opinion comes out in several pages and it is evidently pervaded by her strong sincere Christian faith.

Other beautiful classic novels proposing tragic stories of fallen women, also published in the Victorian Age, are THE SCARLET LETTER by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1850) and TESS OF THE D’URBEVILLES by Thomas Hardy (1891).

RELATED POSTS & SITES

THE WOMAN QUESTION IN THE VICTORIAN AGE

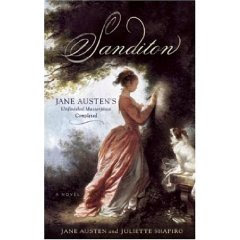

DEIRDRE LA FAYE ON SANDITON

DEIRDRE LA FAYE ON SANDITON

.jpg)